how I conquered gravity and stood up

It was a bit of a shock being born. Upon ejection from my uterine pond I found myself heavy as lead. Astronauts know what I’m talking about. On their return to earth, where the lack of gravity in space renders them weightless as fish suspended in water, it takes weeks for them to regain their pre-travel muscle strength. And I was about to spend months learning to respond to this new force getting to grips with my new airy medium.

Having brought with me from mother’s womb only a reflex twitching of my limbs I was pretty helpless. But my ears had functioned in there, where mother’s voice sounded like whales calling to one another in the depth of the ocean . I especially liked it when she sang Abba songs. Out here sounds were louder and mixed with others quite different in tone.

Light was a new phenomenon that struck the region of my head; and so were the different feelings of warmth and cold – none of which I had names for yet of course.

The leaden heaviness didn’t seem to matter much as large warm creatures held me, while a strange rhythmical movement started up in my chest. Air now needed to circulate through me the same as my mother’s blood had done during the nine months I spent in my water bag. My body twitched and shook as a phenomenally loud noise emanated from my own person as this air business took hold. Many new sensations seemed to set off this noise, except the one I came to recognize as exquisite pleasure – something I’ve been addicted to since that first moment. It was the milk finding its way down my gullet by means of my favourite reflex. As soon as I smelt that milk or felt a touch on my cheek my mouth would start sucking on any proffered nozzle. In view of the inadequacy of language I can only describe this sensation as the purest happiness. There were plenty of other devastating sensations that derived from the business of fuelling myself for growth and development, but here I am concerned with just one aspect of it. If I’d been born in a spacecraft I wouldn’t have needed to grow muscle. On earth I was faced with learning to work with gravity while on land, no longer in water. Where had I been before that? Well, honestly I’ve never been able to remember.

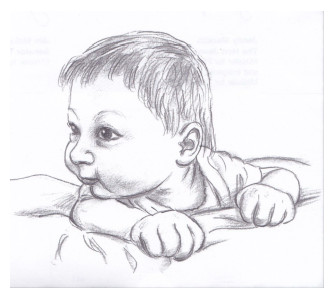

If I wasn’t to remain helpless and dependent on mother’s milk which wouldn’t last forever, I needed to start growing muscle. My head, bombarded as it was with a tumult of sensations whenever I was not asleep, was the first part of me that got going. Sounds, smells and sights got me so entranced that I started growing muscles that would lift my head and move it around, hold it off the ground for a moment. Muscle is funny like that – as if it had a mind of its own. If you constantly want some part of you to move, it’s as though it obliges by growing more fibres.

The new surround-sounds and cinemascopic view that my raised and turning head gave me was pretty exciting; so much so that my twisting trunk and flailing limbs got caught up in the general

The new surround-sounds and cinemascopic view that my raised and turning head gave me was pretty exciting; so much so that my twisting trunk and flailing limbs got caught up in the general

enthusiasm and started asking for more, as though I had the potential to take off into the skies. Doesn’t it always feel like that when you first have the idea – but then it takes an age before you can fulfill your wish. I had to go through months of frustrating practice, repeating movements so my muscles would get the message that I was asking for more. Eventually my forelimbs could contract hard enough to raise the front end of my trunk along with my head, and I spent a few weeksdoing push-ups.

This gave me a far better view which combined with my rollings and twistings and sit-ups and push-ups to propel my trunk serendipitously one day upright onto my pelvis. This is called sitting I discovered from my surrounding warm bodied fellows who got so excited about it, “Look, he’s sitting!” they chorused.

This gave me a far better view which combined with my rollings and twistings and sit-ups and push-ups to propel my trunk serendipitously one day upright onto my pelvis. This is called sitting I discovered from my surrounding warm bodied fellows who got so excited about it, “Look, he’s sitting!” they chorused.

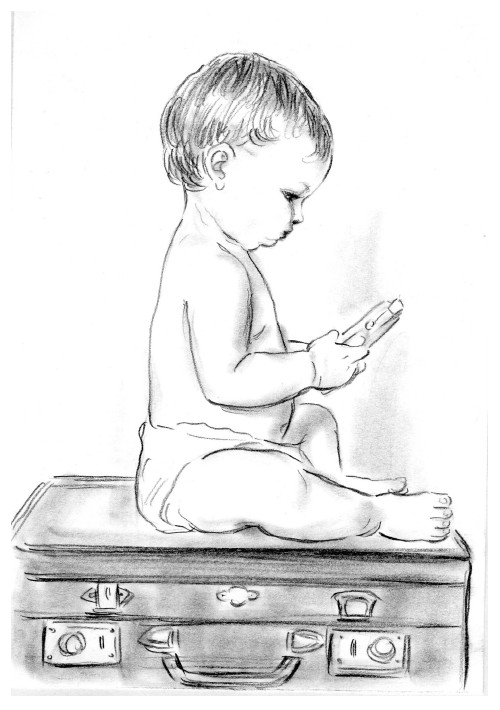

This had come about largely due to the strength in my shoulders and neck. It was tricky refining my muscle control to balance my large head on my top end, but well worth the even better view it gave me as I could turn my head further. In addition my forelimbs were now free to manipulate my magical fingers, and to reach out for things. I was able to lurch deliberately towards some piece of carpet flotsam that attracted me, and to push myself back up onto my pelvis, freeing my forelimbs from their supporting job. Feeling things and bringing them to my mouth for further exploration of taste, texture and dimension became all consuming.

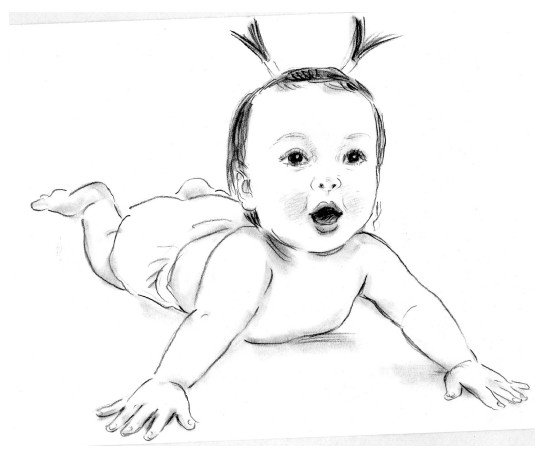

I got so enthusiastic that I toppled constantly onto my belly again and continued the perpetual straightening and bending of my limbs, until one day something seemed to get out of synch. A leg had bent up under me and, as it carried on kicking, it thrust my pelvis up off the ground. There I was, propped up on all fours suddenly, with my neck muscles now strong enough to control the weight of my head stuck way out on one end of me. This new stance clearly had potential for further lurching which gradually evolved into motion. At first I had more oomph in my forelimbs so the pushing back and forth, which was all I could manage at the time, drove me backwards, away from the object of my desire.

So embarrassing! It was quite a puzzle changing random lurching, bracing and kicking into co-ordinated movement. But desire drove me onwards, and I eventually got it all going, setting off into a hugely enlarged world – sometimes at quite a pace I might add. I forgot about flying. Being able to move across the ground to inspect a thousand pieces of flotsam was good enough. Smart as Frederick Alexander I found that if I released my neck muscles, the weight of my head falling caused the muscles of the front end of my trunk to contract and draw me forward, and the resultant stretch along the length of my body would then draw a hind limb up under me; and then if I straightened that same leg, I’d pitch myself forward. It worked! I eventually became fast and smooth in forward motion.

Those were great months of getting around and exploring everything at ground level, on all fours, but I wanted more. Don’t we all? After all, I am human! There were things above me that I could see and hear, not least being these huge warm wonderfully noisy creatures who fed me and who lived up there apparently perfectly balanced on straightened out hind legs! So I was compelled to have a go, and I began pulling myself up on things once again with my now trusty forelimbs and shoulders.

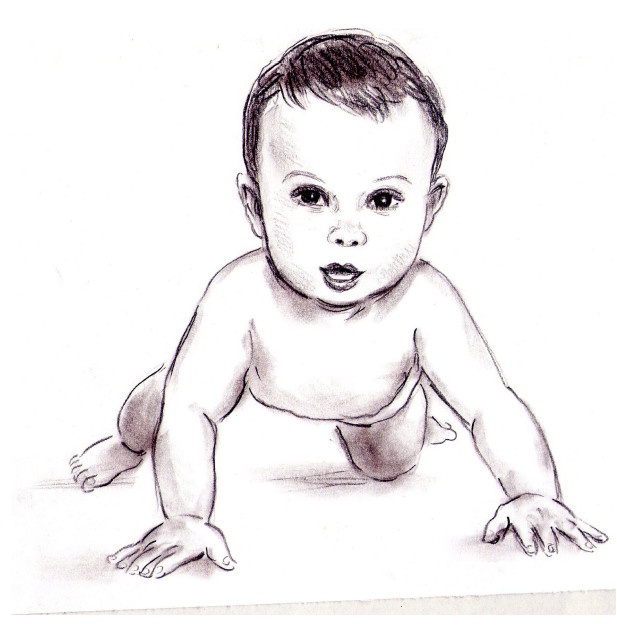

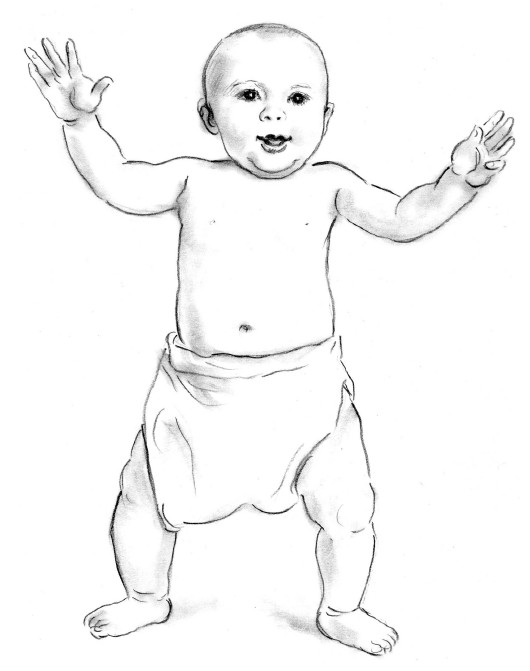

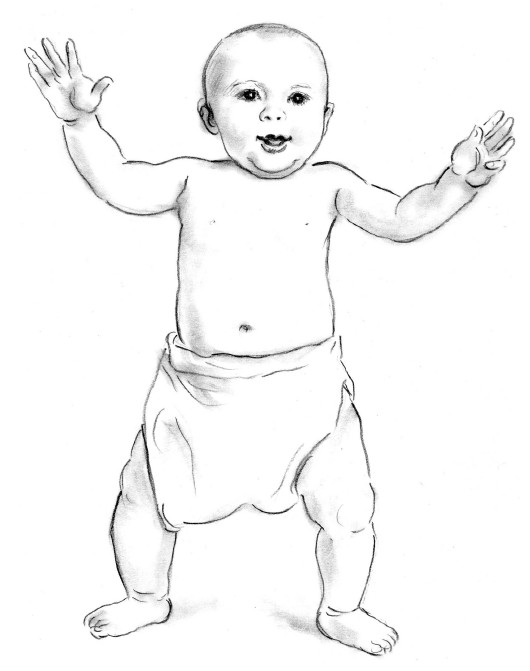

The running around on all fours had strengthened my whole trunk, especially my front end that still had to support my large head while limiting the development of my neck muscles so it would still turn easily. This meant that most of the support for my head still had to come from the upper part of my trunk. I was in fact at this stage better equipped muscularly to stand on my forelegs – as I discovered when first trying out balancing on my hind ones. We humans are never satisfied. What was it that made me want to reach higher? Had I been brought up by a pack of wolves, I wouldn’t have bothered. But here I was in a million-dollar piece of real estate in Sydney, surrounded by creatures of varying sizes, all with the advantage of moving more smoothly and much faster on two legs. They could run! And no way was I going to sacrifice the opportunity to free my hands to touch things and pick them up with my wonderfully skinny digits. So I did it, I got up there. I tried reaching my arms upwards as though if I were to stretch hard enough it might happen. Then I grabbed a table leg, and thanks to my well exercised, excellently developed strong front end I was able to lift my entire trunk off the ground. It didn’t take me long to draw my hind limbs under, and to get the good old plantar reflex on the soles of my feet to do its thing in straightening the legs out for standing on.

There I was, biggest thrill of my life so far, standing fully upright on two legs, a mere year since my traumatic ejection into this new medium. Of course I got carried away at that point, thought I could fly! Instead, even though my neck and shoulder muscles were strong, the task of balancing my head on my taller, lengthened out body needed further adjustment in coordination, so it frequently wobbled off balance and I fell back down again. But by getting up on them again and again, and aided by a few handy reflexes, strength built up in the musculature of my lower trunk and legs enough to stabilize me in my new verticality. You can just imagine the excitement this caused in my large creatures, who would place themselves in front of me and urge me to move towards them.

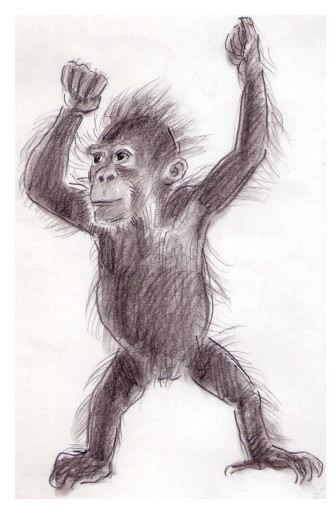

But I was stuck – very much like my primate cousin – until I worked out how to turn my legs at the hip, bring them more directly under my pelvis and discover the amazing knee I’d evolved that would enable me to put one foot in front of the other. That would come after I’d engaged my shoulder girdle hard enough to lift my whole trunk off my still relatively weak hind quarters. I didn’t yet have an equivalent power in my lumber trunk for stable walking. The business of moving forward was rather a matter of keeping my head balanced while enough muscle developed in my hind parts to create the better distribution of tension needed for moving in this new vertical dimension. The most useful part of me remained my front end, the same upper limbs and back that I’d used for getting this far.

But I was stuck – very much like my primate cousin – until I worked out how to turn my legs at the hip, bring them more directly under my pelvis and discover the amazing knee I’d evolved that would enable me to put one foot in front of the other. That would come after I’d engaged my shoulder girdle hard enough to lift my whole trunk off my still relatively weak hind quarters. I didn’t yet have an equivalent power in my lumber trunk for stable walking. The business of moving forward was rather a matter of keeping my head balanced while enough muscle developed in my hind parts to create the better distribution of tension needed for moving in this new vertical dimension. The most useful part of me remained my front end, the same upper limbs and back that I’d used for getting this far.

I needed to continue to move myself upwards , while keeping my head balanced, drawing my trunk upwards so hard that its weight was carried off my pelvis, so all I had to do was lift a heel to bend a knee, balancing momentarily on the other leg while I placed the lifted foot lightly a little in front of me. Maintaining my balance throughout this operation was complex, but accomplishing it was fulfilment of desire.

After a lot of practice I could strut my stuff, even keeping my head balanced while turning my face upwards to drink in the wash of approval from my admiring warm creatures

Mastering head balance while moving on sloped ground was another challenge, not to mention dealing with actual steps! That was a trial that even robots have difficulty with. However, I got there at last and, still dependent on the power in my upper back to keep my legs moving freely under me, I could even run. I continued in this way for the first few years of my life, using my upper back with shoulders spread and for some time even keeping my arms raised to help me along, and to help with balance.

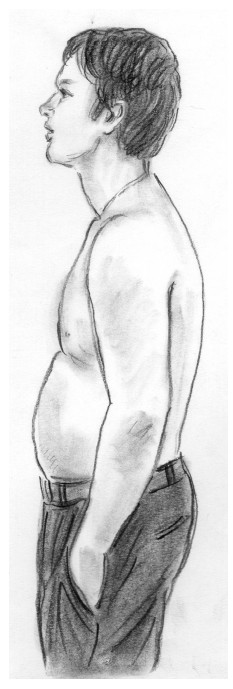

But some years on, due to some annoying side-effects of bipedalism, and especially due to being sat on canted chairs that tilted my pelvis backwards forcing me to pull myself down in front, I let my upper back fall into disuse. I began to use my hands without suspending them properly from my shoulders. It was as if support for my forelimbs was no longer needed now I was upright.

What a mistake that was!

I began to habitually drop down in front, relax my shoulders and lose muscle tone in my back.

This shape came to be recognized as “poor posture”, and there was not much help to sort it until luckily I discovered F M Alexander’s thinking on the subject of use and movement in the upright mammal, which he developed in his now named Alexander Technique.

Understanding helped me to restore full capacity to my trunk, with all proper shaping, and with my shoulders held up and out as they did in my early steps. Alexander himself at 80 years old, illustrates his own beautifully restored upper back as you can see on the front page of this story.

This posture has been negatively described as ‘stiff and held’ by people who assume that since a ‘relaxed’ posture in the adult human is normal it must be OK. But when you compare the cultivation of dropped shoulders in the adult with the child’s lengthened out body, you might think as Alexander did and recognize a failure of maintenance of appropriate shaping as we grow. It’s a matter of continuing to balance the head on the end of the spine – which can only be done if it’s adequately supported by activating the musculature that encompasses an opened out shoulder girdle.

Drawings by Yong Heng

Copyright Christine Ackers, Sydney, 2014